Spotlight: Farley Aguilar’s “The Huddle,” 2011

Farley Aguilar

Farley Aguilar

The Huddle, 2011

Ink on Mylar

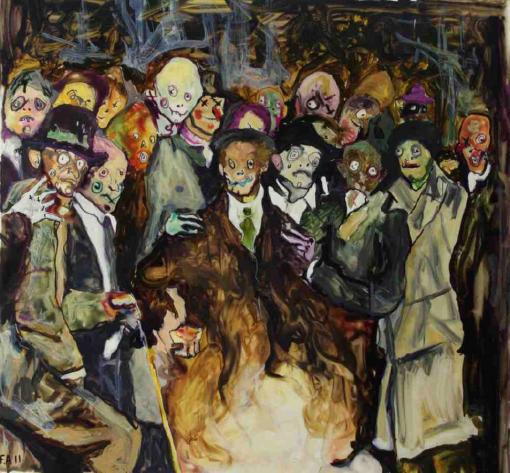

“I think that deep down I don’t trust people and I certainly don’t trust groups,” says Farley Aguilar.[1] This sense of distrust is vividly depicted in Aguilar’s ink composition The Huddle, which illustrates the horrors of being confronted by a group, in which individual identities—and moral centers—are compromised by mob mentality.

The Huddle depicts a placeless group of people crowded around a fire. Aguilar’s Expressionistic brushstrokes create a particularly perplexing picture at the center of the painting. Fix your eyes on the brown-suited individual in the middle of The Huddle—a man, let’s say. His suit seems to be melting, melding with the flames below him. Hands on both of his shoulders—two of the three recognizable appendages in the painting—hold the central figure, but it is unclear whether these hands are pushing him into the fire or holding him back. Even more perplexing is a third anonymous hand reaching into the scene from the left. The figure closest to this hand has the clearest eyes in the crowd, though his opaque gaze does not let us in on The Huddle’s secret. We are forced to ask: to whom does this hand belong? Does it come from within the mob, encroaching toward the central figure to push him down, fully engulf him in flames? Is it the hand of a crowd-aspiring outsider, desperately wishing to join the scene at hand? Or might it be a Salvationist hand—perhaps that of Aguilar himself—intervening in the scene to rescue the man from his fiery demise? Looking at The Huddle, we are left with a sense of dread, wondering: are we complicit in the imminent violence within the image?

The Huddle comes from Aguilar’s “Dogville” series, based, in spirit, on Lars von Trier’s 2003 film of the same name. Aguilar was fascinated by von Trier’s portrayal of an isolated community (in a fictitious, sparse town—Dogville, Colorado) and its deeply troubling treatment of an outsider (played by Nicole Kidman). In von Trier’s rendering, Dogville has no real indications of place—the movie’s set is explicitly transparent with no natural scenery, using only chalk outlines and rare skeletal structures to conjure the town’s environment; Dogville is, at once, everywhere and nowhere, though the film’s characters seem to inhabit a stylized version of Dust Bowl-era America. This universalizing fantasy allows von Trier—and, subsequently, Aguilar—to make a broad indictment of American moral bankruptcy through group mentality, using the violence in Dogville as an allegory for the hypocrisy of American society. Dogville need not be a place; it may be, instead, a way of being in the world.

Still from Dogville, directed by Lars von Trier, 2003

Aguilar, for whom movies are an important source of artistic inspiration, takes up von Trier’s Dogville as subject, showing the “anesthetized state of mind” of Dogville’s placeless denizens in nightmarish scenes of masked groups.[2] The mask—the clownishly menacing, opaque faces placed on The Huddle’s mob of seemingly regular bodies—creates a conscious separation between the subject and the viewer, disrupting the legibility of the painted figures. Are they alive? Possessed? Aguilar might argue, “yes.” The individual, to Aguilar, is always at risk of being subsumed by the group, which, in order to defend itself from outside infiltration, socializes its members into distrusting those outside of it; such tension, in a group setting, can easily erupt in violence. Accordingly, the threat of violence is eerily present in Aguilar’s paintings.

Born in Nicaragua, raised in Miami, Aguilar is a self-taught artist; his only “formal training” took place in a high school art class. But he has always been engaged in play and interested in narrative, perhaps to quell the feelings of “trepidation and uncertainty” that came with being the youngest child in a working-class immigrant family.[3] Thinking back to his childhood, Aguilar remembers, “[One] night I was alone when a thunderstorm knocked out the lights, and I was so scared that I frantically began playing tic-tac-toe to fight the dread. . . . It was a formative experience, and I often use X’s and O’s on subjects’ faces in my paintings to convey anxiety.”[4] These same X’s and O’s can be seen on the faces of The Huddle’s subjects, turning their eyes into symbols of negation and nothingness. Aguilar’s evocative scenes of ghoulish figures and anxious wondering make his work both vital and relevant in an America constantly working to shield itself from terror.

More images of Aguilar’s work can be found at Spinello Projects, his Miami-based gallery.

— Reya Sehgal, Curatorial Assistant

[1] Heike Dempster, “Emerging: Farley Aguilar,” Wonderland, October 20, 2012, http://www.wonderlandmagazine.com/2012/10/emerging-farley-aguilar/.

[2] Spinello Projects, “Farley Aguilar: Artist Statement,” 2011.

[3] Megan Abrahams, “Artist Interview: Farley Aguilar at ALAC, Spinello Projects,” Cartwheel Art, January 21, 2013, http://www.cartwheelart.com/2013/01/21/artist-interview-farley-aguilar-at-alac-spinello-projects/.

[4] Carlos Suarez De Jesus, “Farley Aguilar’s Haunting Images Make Him Miami’s Newest International Art Star,” Broward/Palm Beach New Times, July 3, 2014, http://www.browardpalmbeach.com/2014-07-03/culture/farley-aguilar-s-haunting-images-make-him-miami-s-newest-international-art-star/.