Sue Coe

English, born 1951

Cross Your Heart and Hope to Die, 1997

Lithograph on grey paper, 20 x 15

Gift of Jo-Ann Conklin

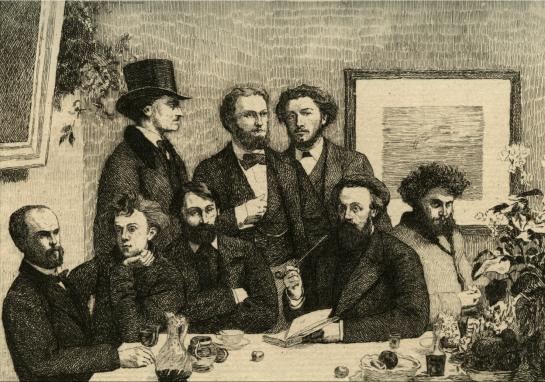

Sue Coe’s Cross Your Heart and Hope to Die (1997) is startling and almost gothic in construction, steeped in a sense of foreboding and dread. A poster of a splayed dead goat, its sliced-open belly facing us, dominates the scene, welcoming us into a darkened room of macabre terrors and animal slaughter. In the lower foreground, a dead rabbit and pig are tied to a metallic table littered with scissors and sharp implements while at left, a pair of human figures in scrubs and masks prop up a slender chimpanzee, leading it from a blinding-white ether into this den of death. Meanwhile, another chimpanzee huddles under the table, curled into a ball, as if wondering when its turn on the table will inevitably come.

This work is a classic example of Coe’s strident animal advocacy translated into a riveting visual image of medical animal testing. Coe’s moralizing, sometimes witty approach to the subject matter of animal rights and welfare has been compared to William Hogarth’s fable-like tales of woe, viciousness, and corruption. Compositionally, Cross Your Heart and Hope to Die most recalls the Third Stage of Hogarth’s famous Four Stages of Cruelty cycle, in which a child’s violence towards animals culminates in violence towards his fellow man.[1] Stylistically, Coe’s prints draw from the graphic tradition of social realism, bringing to mind the intensely political output of the Mexican Taller de Gráfica Popular, Käthe Kollwitz, and Gan Kolski.[2] Instead of focusing on the suffering of the farmer and the manual laborer, however, Coe takes the abused animal, stripped of its dignity and life for fur, meat, or scientific inquiry, as her tragic protagonist. The fright and pain of her pigs and goats—arguably two of her most common subjects—come across as downright human.

Coe hails from the United Kingdom and now resides in New York. She grew up in a working-class community near a local slaughterhouse, which alerted her early on to what she has railed against through art: the horrors of the meat industry. As she wrote of her childhood in her 1996 monograph Dead Meat: “the smell of hogs seeped into everything—clothes and hair […] there was the heavy smell of blood, which hung in the air for two days. As a child, I thought they would slaughter all the pigs they had, then stop. I didn’t understand the regularity of it.[3] One of her most striking paintings, My Mother and I Watch a Pig Escape from the Slaughterhouse (2006), recounts the day Coe and her mother observed a pig attempt to save its own life by running out into the street, chased by slaughterhouse workers in bloody clothes and surrounded by laughing pedestrians. Of that day, she recalled: “maybe this was the first time I saw all was not right with the world.”[4]

Since then, Coe has used her artistic practice to call attention to not only the abuse of animals in the meat industry, but also to the society-wide mindset that permits the designation of nonhuman animals (a preferred term of the animal rights movement[5] ) as less deserving of rights. Dead Meat traces her journey with a sketchpad through various slaughterhouses in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. While cameras would never have been allowed inside these institutions, managers underestimated the power of Coe’s drawings and readily allowed her access.[6] A more recent monograph, The Animals’ Vegan Manifesto (2017), almost wordlessly depicts the uprising of formerly caged animals as they escape their shackles, clip the barbed-wire fences, and seek freedom in a glorious vegan world. Coe has also addressed other political topics in her work, including the arms industry, the administration of George W. Bush, the life of Malcolm X, and sexual violence against women. As Coe stated in a recent interview, “the enormity of the crime against other animals, against the poor, can only be described by art.”[7]

-Deborah Krieger, Public Humanities MA ’21

[1] “Hogarth: Hogarth’s Modern Moral Series, The Four Stages of Cruelty,” Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/hogarth/hogarth-hogarths-modern-moral-series/hogarth-hogarths-4

[2] “Gan Kolski,” Ackland Museum of Art at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, https://ackland.org/education/special-projects/america-seen/kolski/

[3] Sue Coe, Dead Meat (New York and London: Four Walls Eight Windows), 1995, pp. 38-39.

[4] Sue Coe, Dead Meat, 40.

[5] David Nibert, “Introduction,” in Animal Oppression and Capitalism, Volume 1: The Oppression of Nonhuman Animals as Sources of Food, edited by David Nibert (Santa Barbara, California: Praeger), 2017, xviii.

[6] Sue Coe, “Acknowledgements,” in Dead Meat, v.

[7] Sue Coe, “Rendering Cruelty in Art and Politics: A Conversation with Sue Coe,” interview with Michael John Addario, Animal Liberation Currents, July 10, 2017, https://animalliberationcurrents.com/rendering-cruelty-art-politics/

Further reading/bibliography:

Baker, Steve. Artist Animal. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Clyne, Catherine. “At Home with Sue Coe.” Satya, June 1999. http://www.satyamag.com/june99/sat.59.coe.html

Coe, Sue. Dead Meat. New York and London: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1995.

Coe, Sue. “Rendering Cruelty in Art and Politics: A Conversation with Sue Coe.” Interview with Michael John Addario. Published in Animal Liberation Currents, July 10, 2017. https://animalliberationcurrents.com/rendering-cruelty-art-politics/

Coe, Sue. The Animals’ Vegan Manifesto. New York and London: OR Books, 2017.

Eisenmann, Stephen F. The Ghosts of Our Meat—Sue Coe. Carlisle, PA: The Trout Gallery, Dickinson College, 2013. Catalogue accompanying the exhibition The Ghosts of Our Meat—Sue Coe at the Trout Gallery, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA, which ran from November 1, 2013–February 8, 2014.

Francione, Garl L. Introduction to Animal Rights. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000.

Francione, Gary L., and Robert Garner. The Animal Rights Debate: Abolition or Regulation? New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

Kunizar, Alice. “Where is the Animal after Post-Humanism? Sue Coe and the Art of Quivering Life.” The New Centennial Review, Vol. 11, No. 2, Animals . . . In Theory (fall 2011), pp. 17-40.

McCoy, Ann. “Sue Coe: Graphic Resistance.” The Brooklyn Rail, August 2018. Accessed via https://brooklynrail.org/2018/07/artseen/Sue-Coe

Meyer, Jerry D. “Profane and Sacred: Religious Imagery and Prophetic Expression in Postmodern Art.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. 65, No. 1 (Spring, 1997), pp. 19-46.

Milotes, Diane. What May Come: The Taller de Gráfica Popular and the Mexican Political Print. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2014. Catalogue accompanying the exhibition What May Come: The Taller de Gráfica Popular and the Mexican Political Print at the Art Institute of Chicago, which ran from July 4–October 12, 2014.

Ed. Nibert, David. Animal Oppression and Capitalism, Volume 1: The Oppression of Nonhuman Animals as Sources of Food. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger, 2017.

Wye, Deborah. Committed to Print: Social and Political Themes in Recent American Printed Art. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1998. Catalogue accompanying the exhibition Committed to Print at the Museum of Modern Art, which ran from January 31–April 19, 1988.

“Gan Kolski.” Ackland Museum of Art at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://ackland.org/education/special-projects/america-seen/kolski/

“Hogarth: Hogarth’s Modern Moral Series, The Four Stages of Cruelty.” Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/hogarth/hogarth-hogarths-modern-moral-series/hogarth-hogarths-4